Ali Abdullah Saleh

Ali Abdullah Saleh | |

|---|---|

| علي عبدالله صالح | |

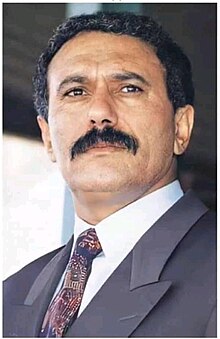

Saleh in 1988 | |

| President of Yemen | |

| In office 22 May 1990 – 27 February 2012 | |

| Prime Minister | |

| Vice President | |

| Preceded by |

|

| Succeeded by | Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi |

| 4th President of North Yemen | |

| In office 18 July 1978 – 22 May 1990 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Vice President | Abdul Karim Abdullah al-Arashi |

| Preceded by | Abdul Karim Abdullah al-Arashi |

| Succeeded by | Himself as President of Yemen |

| Chairman of the General People's Congress | |

| In office 24 August 1982[1] – 4 December 2017 Disputed with Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi starting 21 October 2015[2][3] | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Sadeq Amin Abu Rass |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ali Abdullah Saleh 21 March 1947 Beit al-Ahmar, Sanhan District, North Yemen |

| Died | 4 December 2017 (aged 70) Sanaa, Yemen |

| Manner of death | Assassination by firearm |

| Political party | General People's Congress |

| Spouse |

Asma (m. 1964) |

| Children | 7, including Ahmed |

| Nickname | Affash |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Years of service | 1958–2017 |

| Rank | Field marshal |

| Battles/wars | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

Ali Abdullah Saleh (Arabic: , ʿAlī ʿAbdullāh Ṣāliḥ; 21 March 1947[4][5][note 1] – 4 December 2017), commonly known by his last name Affash (Arabic: عفاش),[6] was a Yemeni politician who served as the first President of the Republic of Yemen, from Yemeni unification on 22 May 1990, to his resignation on 27 February 2012, following the Yemeni revolution.[7] Previously, he had served as the fourth and last President of the Yemen Arab Republic (North Yemen), from July 1978 to 22 May 1990, after the assassination of President Ahmad al-Ghashmi.[8] al-Ghashmi had earlier appointed Saleh as military governor in Taiz.[9]

Saleh developed deeper ties with Western powers, especially the United States, during the War on Terror. Islamic terrorism may have been used and encouraged by Ali Abdullah Saleh in order to win Western support and for disruptive politically motivated attacks.[10][11] In 2011, in the wake of the Arab Spring, which spread across North Africa and the Middle East (including Yemen), Saleh's time in office became increasingly precarious, until he was eventually ousted as President in 2012. He was succeeded by Abdrabbuh Mansur al-Hadi, who had been serving as vice president since 1994, and acting president since 2011.[12]

In May 2015, Saleh openly allied with the Houthis (Ansar Allah) during the Yemeni Civil War,[13] in which a protest movement and subsequent insurgency succeeded in capturing Yemen's capital, Sanaa, causing President al-Hadi to resign and flee the country. In December 2017, he declared his withdrawal from his coalition with the Houthis and instead sided with his former enemies – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and President al-Hadi.[14]

On 4 December 2017, during a battle between Houthi and Saleh supporters in Sanaa, the Houthis accused Saleh of treason, and he was killed by a Houthi sniper.[15] Reports were that Saleh was killed while trying to flee his compound in a car; however, this was denied by his party officials, who said he was executed at his house.[16][17][18]

Early life

[edit]

Ali Abdullah Saleh was born on 21 March 1947[5] to a poor family[19] in Beit al-Ahmar village[20] (Red House village)[21] from the Sanhan (سنحان) clan (Sanhan District), whose territories lie some 20 kilometers southeast of the capital, Sanaa. Saleh's father, Abdallah Saleh died after he divorced Ali Abdullah's mother when Saleh was still young.[19][22] His mother later remarried her deceased former husband's brother, Muhammad Saleh, who soon became Saleh's mentor and stepfather.[22] Saleh's brother Mohammed was a major general and had three children: Yahya, Tareq, and Ammar, who all served under Saleh during his rule.[23]

Saleh's cousin, Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar from the Al Ahmar family, which is also part of the Sanhan clan is often confused with the same-named leading family of the Hashid tribe, with which the Sanhan clan was an ally.[20] The Hashid tribe, in turn, belongs to the larger Yemeni parent group, the Kahlan tribe. The clans Sanhan and Khawlan are said to be related.[20]

Ali Abdallah Saleh married Asama Saleh in 1964.[24]

Military career and rise to the presidency

[edit]Saleh received his primary education at Ma'alama village before leaving to join the North Yemeni Armed Forces in 1958 as an infantry soldier and was admitted to the North Yemen Military Academy in 1960.[19][25] Three years later, in 1963, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in armoured corps.[25] He participated in the Nasserist-inspired military coup of 1962, which was instrumental in the removal of King Muhammad al-Badr and the establishment of the Yemen Arab Republic. During the North Yemen Civil War, he attained the rank of major by 1969. He received further training as a staff officer in the Higher Command and staff C Course in Iraq, between 1970 and 1971, and was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He became a full colonel in 1976 and was given command of a mechanised brigade. In 1977, the President of North Yemen, Ahmad al-Ghashmi, appointed him as military governor of Taiz.[20] After al-Ghashmi was assassinated on 24 June 1978, Colonel Saleh was appointed to be a member of the four-man provisional presidency council and deputy to the general staff commander.[20][25] On 17 July 1978, Saleh was elected by the Parliament to be the President of the Yemen Arab Republic, while simultaneously holding the positions of chief of staff and commander-in-chief of the armed forces.[25]

Governance in the Middle East and North Africa: A Handbook describes Saleh as being neither from a "sheikhly family" nor a "large or important tribe" either, but instead rising to power through "his own means", and creating a patronage system with his family at the top.[26] His seven brothers were placed "in key positions", and later he relied on "sons, daughters, sons-in-law and nephews".[26] Beneath the positions occupied by his extended family, Saleh "relied heavily on the loyalty" of two tribes, his own Sanhan tribe and the Hamdan San'a tribe of his mentor, the late president al-Ghashmi.[26] The New York Times Middle Eastern correspondent Robert F. Worth described Saleh as reaching an understanding with powerful feudal "big sheikhs" to become "part of a Mafia-style spoils system that substituted for governance".[27] Robert Worth accused Saleh of exceeding the aggrandisement of other Middle Eastern strongmen by managing to "rake off tens of billions of dollars in public funds for himself and his family" despite the extreme poverty of his country.[28]

North Yemen presidency

[edit]

On 10 August 1978, Saleh ordered the execution of 30 officers who were charged with being part of a conspiracy against his rule.[20] Saleh was promoted to major general in 1980, elected as the secretary-general of the General People's Congress party on 30 August 1982, and re-elected president of the Yemen Arab Republic in 1983.[25]

The People's Constituent Assembly, which had been created somewhat earlier, selected Col. Ali Abdullah Saleh as al-Ghashmī’s successor. Despite early public skepticism and a serious coup attempt in late 1978, Saleh managed to conciliate most factions, improve relations with Yemen's neighbours, and resume various programs of economic and political development and institutionalization. More firmly in power in the 1980s, he created the political organization that was to become known as his party, the General People's Congress (GPC), and steered Yemen into the age of oil.

In the late 1980s, Saleh was under considerable international pressure to permit his country's Jewish citizens to travel freely to places abroad. Passports were eventually issued to them, which facilitated their unrestricted travel.

Unified Yemen presidency

[edit]

The decline of the Soviet Union severely weakened the status of South Yemen, a communist-originated state, and, in 1990,[29] the North and South agreed to unify after years of negotiations. The South accepted Saleh as President of the unified country, while Ali Salim al-Beidh served as the Vice President and a member of the Presidential Council.[30][31]

After Iraq lost the Gulf War, Yemeni workers were deported from Kuwait by the restored government.[32]

In the 1993 parliamentary election, the first held after unification, Saleh's General People's Congress won 122 of 301 seats.[33] South disagreeing with their party's third place position, started a brief civil-war until 1994 when Saleh's army ended the insurgency.[12]

Terrorist links

[edit]

Around 1994, jihadists from Ayman al-Zawahiri's Egyptian Islamic Jihad attempted to regroup in Yemen following a harsh crackdown in Egypt. In this, they were tacitly supported by the regime of Ali Abdullah Saleh, as he found them useful in his fight against southern separatists in the civil war of 1994.[34] After using Islamic militants to repress the separatist Yemeni Socialist Party and keep the country under his rule, Saleh turned a blind eye to their activities and allowed their sympathizers to work in his intelligence services.[35]

Military promotion

[edit]On 24 December 1997, Parliament approved Saleh's promotion to the rank of field marshal,[20][25] making him the highest-ranking military officer in Yemen.[20]

He became Yemen's first directly elected president in the 1999 presidential election, winning 96.2% of the vote.[33]: 310 The only other candidate, Najeeb Qahtan Al-Sha'abi, who was the son of Qahtan Muhammad al-Shaabi, the former president of South Yemen. Though a member of Saleh's General People's Congress (GPC) party, Najeeb ran as an independent.[36]

1999 election

[edit]

After the 1999 elections, the Parliament passed a law extending presidential terms from five to seven years, extending parliamentary terms from four to six years, and creating a 111-member, presidentially-appointed council of advisors with legislative power.[25] This move prompted Freedom House to downgrade their rating of political freedom in Yemen from 5 to 6.[37]

2006 election

[edit]

In July 2005, during the 27th-anniversary celebrations of his presidency, Saleh announced that he would "not contest the [presidential] elections" in September 2006. He expressed hope that "all political parties – including the opposition and the General People's Congress – find young leaders to compete in the elections because we have to train ourselves in the practice of peaceful succession."[38] However, in June 2006, Saleh changed his mind and accepted his party's nomination as the presidential candidate of the GPC, saying that when he initially decided not to contest the elections his aim was "to establish ground for a peaceful transfer of power", and that he was now, however, bowing to the "popular pressure and appeals of the Yemeni people." Political analyst Ali Saif Hasan said that he had been "sure [President Saleh] would run as a presidential candidate. His announcement in July 2005 – that he would not run – was exceptional and unusual." Mohammed al-Rubai, head of the opposition supreme council, said the president's decision "show[ed] that the president wasn't serious in his earlier decision. I wish he hadn't initially announced that he would step down. There was no need for such farce."[36]

In the 2006 presidential election, held on 20 September, Saleh won with 77.2% of the vote. His main rival, Faisal bin Shamlan, received 21.8%.[25][39] Saleh was sworn in for another term on 27 September 2006.[40]

In December 2005, Saleh stated in a nationally televised broadcast that only his personal intervention had prevented a U.S. occupation of the southern port of Aden after the 2000 USS Cole bombing, stating "By chance, I happened to be down there. If I hadn't been, Aden would have been occupied as there were eight U.S. warships at the entrance to the port."[41] However, transcripts from the United States Senate Committee on Armed Services stated that no other warships were in the vicinity at the time.[42]

Colluding with terrorists

[edit]

After 9/11, Saleh sided with America in the War on Terror. Following the mysterious "escape" of Al Qaeda convicts in Yemeni custody during the 2006 Yemen prison escape, Saleh demanded more American money and support in order to catch the fugitives.[35]

In an investigative documentary allegations were made that Saleh's government supported and directly helped Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).[11]

An informant for the National Security Bureau (NSB) and Political Security Organization (PSO) made these allegations.

Hani Muhammad Mujahid, 38, told Al Jazeera that "many Al-Qaeda leaders were under the complete control of Ali Abdullah Saleh", "Ali Abdullah Saleh turned Al-Qaeda into an organized criminal gang. He was not only playing with the West. He was playing with the entire world".

Richard Barrett, who was with Britain's MI6 intelligence agency before becoming director of the Al-Qaeda Monitoring Team for the UN, described Mujahid's story of his background in Afghanistan, his return to Yemen and his involvement with AQAP as "credible". The attack on the U.S. Embassy in 2008 was funded by Saleh's nephew and Al Qaeda leaders had close relationships with him. The informant also gave critical intelligence on terrorist movements, attacks and leaders but no action was taken.

Ousted from the presidency

[edit]Protests

[edit]In early 2011, following the Tunisian revolution which resulted in the overthrow of the long-time Tunisian president, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, opposition parties attempted to do the same in Yemen. Opposition elements started leading protests and demanding that Saleh end his three-decade-long rule because of the perceived lack of democratic reform, widespread corruption and human rights abuses carried out by him and his allies.[43][failed verification][44] His net worth was estimated to be between 32 and 64 billion dollars with his money spread across multiple accounts in Europe and abroad.[45]

On 2 February 2011, facing a major national uprising, Saleh announced that he would not seek re-election in 2013, but would serve out the remainder of his term.[46] In response to government violence against protesters, eleven MPs of Saleh's party resigned on 23 February.[47] By 5 March, this number had increased to 13, as well as the addition of two deputy ministers.[48]

On 10 March 2011, Saleh announced a referendum on a new constitution, separating the executive and legislative powers.[49] On 18 March, at least 52 people were killed and over 200 injured by government forces when unarmed demonstrators were fired upon in the university square in Sana'a. The president claimed that his security forces were not at the location, and blamed local residents for the massacre.[50][failed verification]

On 7 April 2011, the United States diplomatic cables leak reported the plans of Hamid al-Ahmar, the Islah Party leader, prominent businessman, and de facto leader of Yemen's largest tribal confederation claiming that he would organize popular demonstrations throughout Yemen aimed at removing President Saleh from power.[51]

On 23 April 2011, facing massive nationwide protests, Saleh agreed to step down under a 30-day transition plan in which he would receive immunity from criminal prosecution.[52][53] He stated that he planned to hand power over to his vice president, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi as part of the deal.[54]

On 18 May 2011, he agreed to sign a deal with opposition groups, stipulating that he would resign within a month;[55] On 23 May, Saleh refused to sign the agreement, leading to renewed protests and the withdrawal of the Gulf Cooperation Council from mediation efforts in Yemen.[56]

Assassination attempt and resignation

[edit]On 3 June 2011, Saleh was injured in a bomb attack on his presidential compound. Multiple C-4 (explosive) charges were planted inside the mosque and one exploded when the president and major members of his government were praying.[31] The explosion killed four bodyguards and former prime minister, Abdul Aziz Abdul Ghani (who died later of his wounds), deputy prime ministers, head of the Parliament, governor of Sanaa and many more.[42] Saleh suffered burns and shrapnel injuries, but survived, a result that was confirmed by an audio message he sent to state media in which he condemned the attack, but his voice clearly revealed that he was having difficulty in speaking.[57] Government officials tried to downplay the attack by saying he was lightly wounded. The next day he was taken to a military hospital in Saudi Arabia for treatment.[57] According to U.S. government officials, Saleh suffered a collapsed lung and burns on about 40 per cent of his body.[58] A Saudi official said that Saleh had undergone two operations: one to remove the shrapnel and a neurosurgery on his neck.[59]

On 4 June 2011, Vice President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi was appointed as acting president, while Saleh remained the President of Yemen.[60]

On 7 July 2011, Saleh appeared for his first live television appearance since his injury. He appeared badly burned and his arms were both bandaged. In his speech, he welcomed power-sharing but stressed it should be "within the framework of the constitution and in the framework of the law".[61] On 19 September 2011, he was pictured without bandages, meeting King Abdullah.[62]

On 23 September 2011, Yemeni state television announced that Saleh had returned to the country after three months amid increasing turmoil in a week that saw increased gun battles on the streets of Sana'a and more than 100 deaths.[63]

Saleh said on 8 October 2011, in comments broadcast on Yemeni state television, that he would step down "in the coming days". The opposition expressed skepticism, however, and a government minister said Saleh meant that he would leave power under the framework of a Gulf Cooperation Council initiative to transition toward democracy.[64]

On 23 November 2011, Saleh flew to Riyadh in neighbouring Saudi Arabia to sign the Gulf Cooperation Council plan for political transition, which he had previously spurned. Upon signing the document, he agreed to legally transfer the office and powers of the presidency to his deputy, Vice President Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi.[31] The agreement also led to the formation of a government divided by Saleh's political party (GPC) and the JMP.[65]

It was reported that Saleh had left Yemen on 22 January 2012 for medical treatment in New York City.[66] He arrived in the United States six days later.[67] After his deputy Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi won the 2012 Yemeni presidential election on 21 February 2012 running unopposed, Saleh formally ceded power to him and stepped down as the President of Yemen on 27 February 2012, pledging to support efforts to "rebuild" the country still reeling from months of violence.[8]

Post-presidency

[edit]In February 2013, Saleh opened a museum documenting his 33 years in power, located in a wing of the Al Saleh Mosque in Sanaa.[42] One of the museum's central display cases exhibits a pair of burnt trousers that Saleh was wearing at the time of his assassination attempt in June 2011.[31] Other displays include fragments of shrapnel that were taken out of his body during his hospital treatment in Saudi Arabia, as well as various gifts given to Saleh by kings, presidents and world leaders over the course of his rule.[68]

Later that year, in October, the United Nations Special Envoy to Yemen, Jamal Benomar said that Saleh and his son have the right to run in the next Yemeni presidential election, as the 2011 deal does not cover political incapacitation.[69]

Saleh was a behind-the-scenes leader of the Houthi takeover in Yemen led by Zaydi Houthi forces. Tribesmen and government forces loyal to Saleh joined the Houthis in their march to power.[70] The United Nations Security Council imposed sanctions on Saleh in 2014, accusing him of threatening peace and obstructing Yemen's political process, subjecting him to a global travel ban and an asset freeze.[71] On 28 July 2016, Saleh and the Houthi rebels announced a formal alliance to fight the Saudi-led military coalition, run by a Supreme Political Council of 10 members – made up of five members from Saleh's General People's Congress, and five from the Houthis.[72] The members were sworn in on 14 August 2016.[73]

Death

[edit]Houthi spokesperson Mohamed Abdel Salam stated that his group had spotted messages between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Saleh three months before his death. He told the Qatari channel Al-Jazeera that there was communications between Saleh, the UAE and a number of other countries such as Russia and Jordan through encrypted messages.[74] The alliance between Saleh and the Houthi broke down in late 2017,[75] with armed clashes occurring between former allies in Sana'a from 28 November.[76] Saleh declared his split from the Houthi movement in a televised statement delivered on 2 December, calling on his supporters to take back the country[77] and expressed his openness to a dialogue with the Saudi Arabian-led coalition.[75]

On 4 December 2017, Saleh's house in Sana'a was assaulted by fighters of the Houthi movement, according to residents.[78] Saleh was killed on his way to Marib while trying to flee into Saudi-controlled territories after a rocket-propelled grenade struck and disabled his vehicle in an ambush and he was subsequently shot in the head by a Houthi sniper, something his party denied.[79] The Houthis published a video allegedly depicting Saleh's body with a gunshot wound to the head.[80][81] His death was confirmed by a senior aide to Saleh, and also by Saleh's nephew.[31][42] His death has been described by The Economist as an embarrassment in a string of Saudi foreign policy failures under Mohammad bin Salman.[82]

Saleh's home was captured by Houthis before he fled. Officials of his party General People's Congress, while confirming his death, stated that a convoy he and other party officials were travelling in was attacked by Houthis as they fled towards his hometown Sanhan. Houthi leader Abdul Malik al-Houthi meanwhile celebrated Saleh's death and called it "the day of the fall of the treasonous conspiracy". He also stated that his group had "no problem" with the GPC or its members. Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi offered condolences for Saleh's death and called for an uprising against the Houthis.[83] The Houthis accused the UAE of dragging Saleh to "this humiliating fate."[84]

On 9 December 2017, he was buried in Sana'a, according to an official.[85] A Houthi commander reported that the burial was held in strict conditions with no more than 20 people attending.[86]

In popular culture

[edit]The Chinese 2018 movie Operation Red Sea is about the conflict in Yewaire, a country loosely based on Yemen,[87] with a coup launched by General Sharaf, who was based on Saleh but never made an appearance.

Honours

[edit]National honours

[edit]Foreign honours

[edit] Cuba: Medal of the Order of José Martí[89]

Cuba: Medal of the Order of José Martí[89] Libya: First Class of the Order of the Grand Conqueror[90]

Libya: First Class of the Order of the Grand Conqueror[90] Tunisia: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Seventh of November

Tunisia: Grand Cordon of the Order of the Seventh of November United Arab Emirates: Collar of the Order of Zayed[91]

United Arab Emirates: Collar of the Order of Zayed[91] Two Sicilies Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (defunct honour)

Two Sicilies Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (defunct honour)

Two Sicilian Royal Family: Recipient of the Two Sicilian Royal Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George Benemerenti Medal, 1st Class[88]

Two Sicilian Royal Family: Recipient of the Two Sicilian Royal Sacred Military Constantinian Order of Saint George Benemerenti Medal, 1st Class[88] Two Sicilian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Francis I[88]

Two Sicilian Royal Family: Knight Grand Cross of the Royal Order of Francis I[88]

Wealth

[edit]The UN Sanctions Panel said that by 2012 Saleh had amassed a fortune worth $32–60 billion hidden in at least twenty countries, making him one of the richest people in the world. Saleh was gaining $2 billion a year from 1978 to 2012, mainly through illegal methods, such as embezzlement, extortion and theft of funds from Yemen's fuel subsidy programs.[92][93]

Personal life

[edit]He was married to Asma Saleh in 1964, at the age of seventeen. The couple have seven sons, including the eldest Ahmed Saleh (born 1972), former commander of the Republican Guard, once considered a potential successor to his father, and Khaled.

His half-brother, General Mohamed Saleh al-Ahmar was commander of the Yemeni Air Force.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ There is a dispute as to Saleh's date of birth, some saying that it was on 21 March 1942. See: Downing, Terry Reese (1 November 2009). Martyrs in Paradise. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4490-0881-9. However, by Saleh's own confession (an interview recorded in a YouTube video), he was born in 1947.

References

[edit]- ^ Al Yemeni, Ahmed A. Hezam (2003). The Dynamic of Democratisation – Political Parties in Yemen (PDF). Toennes Satz + Druck GmbH. ISBN 3-89892-159-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2021. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Asharq al-Awsat; Muhammad Ali Mohsen (22 October 2015). "The People's Congress meets with Hadi in Riyadh and nominates him as president after Saleh is dismissed". Asharq Al-Awsat (in Arabic). Riyadh, Saudi Arabia and Aden, Yemen. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Tawfeek al-Ganad (20 September 2022). "Weak and Divided, the General People's Congress Turns 40". Sana'a Center For Strategic Studies. Sanaa. Archived from the original on 11 February 2023. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ "Hadha Ma Euthir Ealayh Mae Eali Eabd Allah Salih" هذا ما عثر عليه مع علي عبد الله صالح [This is what was found with Ali Abdullah Saleh]. Alhurra (in Arabic). 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ a b "Security Council 2140 Sanctions Committee Amends Three Entries on Its List, Updates Narrative Summary". www.un.org. United Nations. Archived from the original on 25 June 2021. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/yemen-rebel-leader-former-president-killed-ali-abdullah-saleh-fighting-saudi-arabia-crisis-conflict-latest-a8090721.html

- ^ Riedel, Bruce (18 December 2017). "Who are the Houthis, and why are we at war with them?". Brookings. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ a b "AFP: Yemen's Saleh formally steps down after 33 years". Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ^ Aziz, Mr Sajid (28 July 2015). "Yemen Conundrum". CISS Insight Journal. 3 (1&2): P65–78. Retrieved 12 November 2023.

- ^ Spencer, Richard (11 June 2011). "Yemen defector says terror crisis was manufactured to win western support". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Informant claims former Yemen leader's regime worked with Al-Qaeda". america.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Yemen" (PDF). Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y Cooperación.

- ^ "Yemen's Saleh declares alliance with Houthis". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2015.

- ^ "Yemen: Ex-President Ali Abdullah Saleh killed". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Ahmed, Zayd (5 December 2017). "Deposed strongman Ali Abdullah Saleh killed after switching sides in Yemen's war". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2020.

- ^ Browning, Noah (8 December 2017). "The last hours of Yemen's Saleh". Reuters. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Analysis: Yemen's ex-president Saleh's killing was 'revenge'". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Hakim Almasmari, Tamara Qiblawi and Hilary Clarke. "Yemen's former President Saleh killed in Sanaa". CNN. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ a b c "الرئيس اليمني علي عبد الله صالح" (in Arabic). Al Jazeera. 23 June 2006. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "YEMEN – Ali Abdullah Saleh Al-Ahmar". APS Review Downstream Trends. 26 June 2006. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- ^ "علي عبدالله صالح.. في صور". العربية (in Arabic). 4 December 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ a b Day, Stephen W. (2012). Regionalism and Rebellion in Yemen: A Troubled National Union. Cambridge University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-1070-2215-7. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ "أقارب المخلوع صالح.. الإقالة في مرحلتها الثانية". Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2020.

- ^ "Ali Abdallah Saleh". thetimes. 5 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "President Ali Abdullah Saleh Web Site". Presidentsaleh.gov.ye. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- ^ a b c K. Kadhim, Abbas (2013). Governance in the Middle East and North Africa: A Handbook. Routledge. p. 309. ISBN 9781857435849. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Worth, Robert F. (2016). A Rage for Order: The Middle East in Turmoil, from Tahrir Square to ISIS. Pan Macmillan. p. 105. ISBN 9780374710712. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Worth, Robert F. (2016). A Rage for Order: The Middle East in Turmoil, from Tahrir Square to ISIS. Pan Macmillan. p. 98. ISBN 9780374710712. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Interview of Ali Abdallah Saleh with Eric Rouleau in Sanaa in the early 1990s, eng, Calames, Sound Archives Center, MMSH, http://calames.abes.fr/pub/ms/Calames-202404181618354315

- ^ Burrowes, Robert D. (1987). The Yemen Arab Republic: The Politics of Development, 1962–1986. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-0435-9.

- ^ a b c d e "Yemen's ex-president Saleh shot dead after switching sides in civil war". Reuters. 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Evans, Judith (10 October 2009). "Gulf aid may not be enough to bring Yemen back from the brink". The Sunday Times. London. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011.

- ^ a b Nohlen, Dieter; Grotz, Florian; Hartmann, Christof, eds. (2001). Elections in Asia: A data handbook, Volume I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 309–310. ISBN 978-0-19-924958-9. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- ^ The last refuge: Yemen, al-Qaeda, and America's war in Arabia. 22 May 2013.

- ^ a b Soufan, Ali (5 December 2017). "I Will Die in Yemen". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- ^ a b "In eleventh-hour reversal, President Saleh announces candidacy". IRIN. 25 June 2006. Archived from the original on 5 January 2008. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ "Freedom in the World – Yemen (2002)". Freedom House. 2002. Archived from the original on 21 March 2011.

- ^ "Yemen leader rules himself out of polls". Al Jazeera. 17 July 2005. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ "Saleh re-elected president of Yemen". Al Jazeera. 23 September 2006. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2010.

- ^ "Yemeni president takes constitutional oath for his new term". Xinhua News Agency. 27 September 2006. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012.

- ^ "US mulled occupying Aden after Cole bombing: Yemen". Khaleej Times. 1 December 2005. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Yemen's former President Ali Abdullah Saleh killed trying to flee Sanaa". CNN. 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Yemen: Protests intensify after arrest of journalist Tawakkol Karman Archived 4 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Global Post, 23 January 2011.

- ^ Finn, Tom (23 January 2011). "Yemen arrests anti-government activist". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ "Is Yemen's Saleh really worth $64 billion?". Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ Almasmari, Hakim (2 February 2011). "Yemeni President won't Run Again". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Yemen protest: Ruling party MPs resign over violence". BBC News. 23 February 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Yemen MPs quit ruling party Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Al Jazeera, 3 March 2011.

- ^ 'New constitution for Yemen' Archived 10 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Al Jazeera, 10 March 2011

- ^ "Breaking News, World News and Video from Al Jazeera". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ "WikiLeaks Cable: YEMEN: HAMID AL-AHMAR SEES SALEH AS WEAK AND ISOLATED, PLANS NEXT STEPS". The Washington Post. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Birnbaum, Michael (23 April 2011). "Yemen's President Saleh agrees to step down in return for immunity". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 July 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ "Yemen President Ali Abdullah Saleh defiant over exit". BBC News. 24 April 2011. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ "Yemeni President Saleh signs deal on ceding power". BBC News. 23 November 2011. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "YEMEN: Deal outlined for President Ali Abdullah Saleh to leave within a month". Los Angeles Times. 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ^ "Sky News, 23 May 2011". Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- ^ a b "Wounded Yemeni president in Saudi Arabia". Al Jazeera. 5 June 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ "Sources: Yemeni head Saleh has collapsed lung, burns over 40% of body". CNN. 7 June 2011. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ "Yemeni president flees nation for medical treatment". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- ^ "Al-Hadi acting President of Yemen". Blogs.aljazeera.net. 4 June 2011. Archived from the original on 27 November 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Yemen President Ali Abdullah Saleh appears on TV". BBC News. 7 July 2011. Archived from the original on 21 November 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "Yemeni Protests Continue after Saleh Signs Deal". Archived from the original on 19 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- ^ "Yemen's Saleh calls for ceasefire on return". Al Jazeera. 23 September 2011. Archived from the original on 17 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- ^ "Yemen president 'to step down'". Al Jazeera. 8 October 2011. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- ^ Finn, Tom (23 November 2011). "Yemen president quits after deal in Saudi Arabia". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 March 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ Laura Kasinof (22 January 2012). "Yemen Leader Leaves for Medical Care in New York". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- ^ "Official: Yemen president in US for treatment". The Wall Street Journal. 28 January 2012. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017.

- ^ "Yemen's Saleh opens museum – about himself". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "moslempress.com". ww38.moslempress.com. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ Peter Salisbury. "Yemen's former president Ali Abdullah Saleh behind Houthis' rise". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ^ al-Sayaghi, Mohamed (14 October 2017). "Yemen's ex-president Saleh stable after Russian medics operate". Reuters. Archived from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthi rebels announce alliance with ousted president". Fox News Channel. 28 July 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- ^ "SPC sworn on". SabaNet – Yemen News Agency SABA. 14 August 2016. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ "الحوثيون: رصدنا رسائل بين صالح وأبوظبي قبل 3 شهور" [Houthis: We detected messages between Saleh and Abu Dhabi 3 months ago]. Al Khaleej (in Arabic). 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ a b Faisal Edroos (4 December 2017). "How did Yemen's Houthi-Saleh alliance collapse?". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Leith Fadel (2 December 2017). "Violence escalates in Sanaa as Saleh loyalists battle Houthis". Al Masdar News. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Yemen: Conflict intensifies between former rebel allies". Al Jazeera English. 3 December 2017. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthis blow up ex-president Saleh's house". Reuters.com. 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 25 November 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Houthis reportedly gain control of majority of Sanaa". Al Jazeera. 4 December 2017. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Photo of Corpse Head". mz-mz.net. 5 December 2017. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017.

- ^ "الحوثيون ينشرون صورا وفيديو لمقتل على عبد الله صالح" [Houthis publish photos and a video of the killing of Ali Abdullah Saleh]. Youm7 (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Ali Abdullah Saleh's death will shake up the war in Yemen". The Economist. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ "Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yemen's former leader, killed in Sanaa". BBC. Archived from the original on 8 April 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "ناطق أنصار الله: الإمارات أوصلت زعيم ميليشيا الخيانة إلى هذه النهاية المخزية ولا مشكلة مع المؤتمر" [Nateq Ansar Allah: The UAE brought the leader of the treason militia to this shameful end, and there is no problem with the conference]. almasirah.net (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Yemen's slain ex-President Saleh buried". Business Standard. 9 December 2017. Archived from the original on 12 August 2018. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

- ^ "Yemen rebels bury Saleh in closed funeral: family source". Business Standard. 9 December 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ "Yemen crisis: China evacuates citizens and foreigners from Aden". BBC News. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "President Ali Abdullah Saleh of Yemen is invested into the Order of Francesco I. Duke of Calabria receives highest Yemeni decoration on behalf of the Constantinian Order". constantinian.org.uk. Sacred Military Constantinian Order of St. George. 27 March 2004. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ^ "Recipients of the Order of José Marti". palestine-studies.org. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021.

- ^ صالح والقذافي.. ما أشبه الليلة بالبارحة. alkhaleej.ae (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 16 April 2021.

- ^ "Saleh starts UAE visit (updated)". Emirates News Agency. 31 January 2007. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "Yemen's Saleh Worth $60 Billion Says UN Sanctions Panel". UNTribune.com. 24 February 2015. Archived from the original on 8 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ "Yemen ex-leader 'amassed billions'". BBC News. 25 February 2015. Archived from the original on 18 July 2018. Retrieved 20 June 2018 – via BBC.com.

External links

[edit]- President Ali Abdullah Saleh official Yemen government website

- Ali Abdullah Saleh Appearances on C-SPAN

- Ali Abdullah Saleh collected news and commentary at Al Jazeera English

- Ali Abdullah Saleh collected news and commentary at The Jerusalem Post

- Ali Abdullah Saleh collected news and commentary at The New York Times

- Timeline: Saleh's 32-year rule in Yemen, Reuters, 22 March 2011

- In Yemen, onetime foes united in opposing President Saleh, Sudarsan Raghavan in Sanaa, The Washington Post, 25 March 2011

- Profile: Yemen's Ali Abdullah Saleh, BBC News, 23 April 2011

- 1942 births

- 2017 deaths

- Yemeni anti-communists

- Critics of Islamism

- 20th-century Yemeni politicians

- Deaths by firearm in Yemen

- Field marshals of Yemen

- General People's Congress (Yemen) politicians

- People from Sanaa Governorate

- People of the Yemeni revolution

- Presidents of North Yemen

- Vice presidents of North Yemen

- Presidents of Yemen

- Yemeni Arab nationalists

- Yemeni military personnel killed in the Yemeni civil war (2014–present)

- Yemeni Zaydis

- Saleh family

- People of the North Yemen Civil War

- 20th-century Yemeni military personnel

- 21st-century Yemeni politicians

- Assassinated Yemeni politicians

- Assassinations in Yemen

- Burials in Yemen

- Executed presidents

- Filmed assassinations

- Asian politicians assassinated in the 2010s

- Assassinated presidents in Asia

- 20th-century presidents in Asia

- Politicians assassinated in 2017

- National presidents assassinated in the 21st century