Paddle steamer

A paddle steamer is a steamship or steamboat powered by a steam engine driving paddle wheels to propel the craft through the water. In antiquity, paddle wheelers followed the development of poles, oars and sails, whereby the first uses were wheelers driven by animals or humans.

In the early 19th century, paddle wheels were the predominant way of propulsion for steam-powered boats. In the late 19th century, paddle propulsion was largely superseded by the screw propeller and other marine propulsion systems that have a higher efficiency, especially in rough or open water. Paddle wheels continue to be used by small, pedal-powered paddle boats and by some ships that operate tourist voyages. The latter are often powered by diesel engines.[a]

Paddle wheels

[edit]

Right: Detail of a steamer

The paddle wheel is a large steel framework wheel. The outer edge of the wheel is fitted with numerous, regularly spaced paddle blades (called floats or buckets). The bottom quarter or so of the wheel travels under water. An engine rotates the paddle wheel in the water to produce thrust, forward or backward as required. More advanced paddle-wheel designs feature "feathering" methods that keep each paddle blade closer to vertical while in the water to increase efficiency. The upper part of a paddle wheel is normally enclosed in a paddlebox to minimise splashing.

Types of paddle steamers

[edit]

The three types of paddle wheel steamer are sidewheeler, with one paddlewheel amidships on each side; sternwheeler, with a single paddlewheel at the stern; and (rarely) inboard, with the paddlewheel mounted in a recess amidships.[2]

Sidewheeler

[edit]

The earliest steam vessels were sidewheelers, and the type was by far the dominant mode of marine steam propulsion, both for steamships and steamboats, until the increasing adoption of screw propulsion from the 1850s. Though the side wheels and enclosing sponsons make them wider than sternwheelers, they may be more maneuverable, since they can sometimes move the paddles at different speeds, and even in opposite directions. This extra maneuverability makes side-wheelers popular on the narrower, winding rivers of the Murray–Darling system in Australia, where a number still operate.

European sidewheelers, such as PS Waverley, connect the wheels with solid drive shafts that limit maneuverability and give the craft a wide turning radius. Some were built with paddle clutches that disengage one or both paddles so they can turn independently. However, wisdom gained from early experience with sidewheelers deemed that they be operated with clutches out, or as solid-shaft vessels. Crews noticed that as ships approached the dock, passengers moved to the side of the ship ready to disembark. The shift in weight, added to independent movements of the paddles, could lead to imbalance and potential capsizing. Paddle tugs were frequently operated with clutches in, as the lack of passengers aboard meant that independent paddle movement could be used safely and the added maneuverability exploited to the full.

Sternwheeler

[edit]Although the first sternwheelers were invented in Europe, they saw the most service in North America, especially on the Mississippi River. Enterprise was built at Brownsville, Pennsylvania, in 1814 as an improvement over the less efficient side-wheelers. The second stern-wheeler built, Washington of 1816, had two decks and served as the prototype for all subsequent steamboats of the Mississippi, including those made famous in Mark Twain's book Life on the Mississippi.[3]

Inboard paddlewheeler

[edit]Recessed or inboard paddlewheel boats were designed to ply narrow and snag-infested backwaters. By recessing the wheel within the hull it was protected somewhat from damage. It was enclosed and could be spun at a high speed to provide acute maneuverability. Most were built with inclined steam cylinders mounted on both sides of the paddleshaft and timed 90 degrees apart like a locomotive, making them instantly reversing.

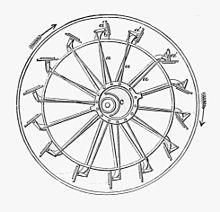

Feathering paddle wheel

[edit]

In a simple paddle wheel, where the paddles are fixed around the periphery, power is lost due to churning of the water as the paddles enter and leave the water surface. Ideally, the paddles should remain vertical while under water. This ideal can be approximated by use of levers and linkages connected to a fixed eccentric. The eccentric is fixed slightly forward of the main wheel centre. It is coupled to each paddle by a rod and lever. The geometry is designed such that the paddles are kept almost vertical for the short duration that they are in the water.[4]

History

[edit]Western world

[edit]

The use of a paddle wheel in navigation appears for the first time in the mechanical treatise of the Roman engineer Vitruvius (De architectura, X 9.5–7), where he describes multigeared paddle wheels working as a ship odometer. The first mention of paddle wheels as a means of propulsion comes from the fourth– or fifth-century military treatise De Rebus Bellicis (chapter XVII), where the anonymous Roman author describes an ox-driven paddle-wheel warship:

Animal power, directed by the resources on ingenuity, drives with ease and swiftness, wherever utility summons it, a warship suitable for naval combats, which, because of its enormous size, human frailty as it were prevented from being operated by the hands of men. In its hull, or hollow interior, oxen, yoked in pairs to capstans, turn wheels attached to the sides of the ship; paddles, projecting above the circumference or curved surface of the wheels, beating the water with their strokes like oar-blades as the wheels revolve, work with an amazing and ingenious effect, their action producing rapid motion. This warship, moreover, because of its own bulk and because of the machinery working inside it, joins battle with such pounding force that it easily wrecks and destroys all enemy warships coming at close quarters.[5]

Italian physician Guido da Vigevano (circa 1280–1349), planning for a new crusade, made illustrations for a paddle boat that was propelled by manually turned compound cranks.[6]

One of the drawings of the Anonymous Author of the Hussite Wars shows a boat with a pair of paddlewheels at each end turned by men operating compound cranks.[7] The concept was improved by the Italian Roberto Valturio in 1463, who devised a boat with five sets, where the parallel cranks are all joined to a single power source by one connecting rod, an idea adopted by his compatriot Francesco di Giorgio.[7]

In 1539, Spanish engineer Blasco de Garay received the support of Charles V to build ships equipped with manually-powered side paddle wheels. From 1539 to 1543, Garay built and launched five ships, the most famous being the modified Portuguese carrack La Trinidad, which surpassed a nearby galley in speed and maneuverability on June 17, 1543, in the harbor of Barcelona. The project, however, was discontinued.[8] 19th century writer Tomás González claimed to have found proof that at least some of these vessels were steam-powered, but this theory was discredited by the Spanish authorities. It has been proposed that González mistook a steam-powered desalinator created by Garay for a steam boiler.[8]

In 1705, Papin constructed a ship powered by hand-cranked paddles. An apocryphal story originating in 1851 by Louis Figuire held that this ship was steam-powered rather than hand-powered and that it was therefore the first steam-powered vehicle of any kind. The myth was refuted as early as 1880 by Ernst Gerland, though still it finds credulous expression in some contemporary scholarly work.[9]

In 1787, Patrick Miller of Dalswinton invented a double-hulled boat that was propelled on the Firth of Forth by men working a capstan that drove paddles on each side.[10]

One of the first functioning steamships, Palmipède, which was also the first paddle steamer, was built in France in 1774 by Marquis Claude de Jouffroy and his colleagues. The 13 m (42 ft 8 in) steamer with rotating paddles sailed on the Doubs River in June and July 1776. In 1783, a new paddle steamer by de Jouffroy, Pyroscaphe, successfully steamed up the river Saône for 15 minutes before the engine failed. Bureaucracy and the French Revolution thwarted further progress by de Jouffroy.

The next successful attempt at a paddle-driven steam ship was by Scottish engineer William Symington, who suggested steam power to Patrick Miller of Dalswinton.[10] Experimental boats built in 1788 and 1789 worked successfully on Lochmaben Loch. In 1802, Symington built a barge-hauler, Charlotte Dundas, for the Forth and Clyde Canal Company. It successfully hauled two 70-ton barges almost 20 mi (32 km) in 6 hours against a strong headwind on test in 1802. Enthusiasm was high, but some directors of the company were concerned about the banks of the canal being damaged by the wash from a powered vessel, and no more were ordered.

While Charlotte Dundas was the first commercial paddle steamer and steamboat, the first commercial success was possibly Robert Fulton's Clermont in New York, which went into commercial service in 1807 between New York City and Albany. Many other paddle-equipped river boats followed all around the world; the first in Europe being PS Comet designed by Henry Bell which started a scheduled passenger service on the River Clyde in 1812.[12]

In 1812, the first U.S. Mississippi River paddle steamer began operating out of New Orleans. By 1814, Captain Henry Shreve[b] had developed a "steamboat" [c] suitable for local conditions. Landings in New Orleans went from 21 in 1814 to 191 in 1819, and over 1,200 in 1833.

The first stern-wheeler was designed by Gerhard Moritz Roentgen from Rotterdam, and used between Antwerp and Ghent in 1827.[13]

Team boats, paddle boats driven by horses, were used for ferries the United States from the 1820s–1850s, as they were economical and did not incur licensing costs imposed by the steam navigation monopoly. In the 1850s, they were replaced by steamboats.[14]

After the American Civil War, as the expanding railroads took many passengers, the traffic became primarily bulk cargoes. The largest, and one of the last, paddle steamers on the Mississippi was the sternwheeler Sprague. Built in 1901, she pushed coal and petroleum until 1948.[15][16][17][18][19]

In Europe from the 1820s, paddle steamers were used to take tourists from the rapidly expanding industrial cities on river cruises, or to the newly established seaside resorts, where pleasure piers were built to allow passengers to disembark regardless of the state of the tide. Later, these paddle steamers were fitted with luxurious saloons in an effort to compete with the facilities available on the railways. Notable examples are the Thames steamers which took passengers from London to Southend-on-Sea and Margate, Clyde steamers that connected Glasgow with the resort of Rothsay and the Köln-Düsseldorfer cruise steamers on the River Rhine. Paddle steamer services continued into the mid-20th century, when ownership of motor cars finally made them obsolete except for a few heritage examples.[20]

Asia

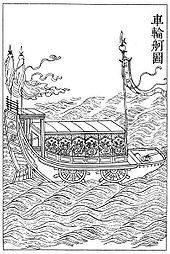

[edit]China

[edit]

The first mention of a paddle-wheel ship from China is in the History of the Southern Dynasties, compiled in the 7th century but describing the naval ships of the Liu Song dynasty (420–479) used by admiral Wang Zhen'e in his campaign against the Qiang in 418 AD. The ancient Chinese mathematician and astronomer Zu Chongzhi (429–500) had a paddle-wheel ship built on the Xinting River (south of Nanjing) known as the "thousand league boat".[21] When campaigning against Hou Jing in 552, the Liang dynasty (502–557) admiral Xu Shipu employed paddle-wheel boats called "water-wheel boats". At the siege of Liyang in 573, the admiral Huang Faqiu employed foot-treadle powered paddle-wheel boats. A successful paddle-wheel warship design was made in China by Prince Li Gao in 784 AD, during an imperial examination of the provinces by the Tang dynasty (618–907) emperor.[22] The Chinese Song dynasty (960–1279) issued the construction of many paddle-wheel ships for its standing navy, and according to the British biochemist, historian, and sinologist Joseph Needham:

"...between 1132 and 1183 (AD) a great number of treadmill-operated paddle-wheel craft, large and small, were built, including sternwheelers and ships with as many as 11 paddle-wheels a side,".[23]

The standard Chinese term "wheel ship" was used by the Song period, whereas a litany of colorful terms were used to describe it beforehand. In the 12th century, the Song government used paddle-wheel ships en masse to defeat opposing armies of pirates armed with their own paddle-wheel ships. At the Battle of Caishi in 1161, paddle-wheelers were also used with great success against the Jin dynasty (1115–1234) navy.[24] The Chinese used the paddle-wheel ship even during the First Opium War (1839–1842) and for transport around the Pearl River during the early 20th century.

Bangladesh

[edit]This section needs expansion with: detailed early history. You can help by adding to it. (June 2024) |

Paddle steamers in Bangladesh were first operated by the River Steam Navigation Company Limited in 1878. Many steamers, including the Garrow, Florikan, Burma, Majabi, Flamingo, Kiyi, Mohamend, Sherpa, Pathan, Sandra, Irani, Seal, Lali, and Mekla, dominated the southern rivers. In 1958, Pakistan River Steamers inherited the fleet,[25] some of which were built at the private Garden Rich Dockyard in Kolkata.[26]

After the liberation of Bangladesh, there were around 13 paddle steamers in 1972,[26] nicknamed “the Rockets” for their speed,[27] operated by the newly founded Bangladesh Inland Water Transport Corporation (BIWTC). These included PS Sandra, PS Lali, PS Mohammed, PS Gazi, PS Kiwi, PS Ostrich, PS Mahsud, PS Lepcha, and PS Tern.[26] The steamers served destinations such as Chandpur, Barisal, Khulna, Morrelganj, and Kolkata, from Dhaka.[25]

In the 1980s, the steam engines were replaced with diesel ones, and the wooden paddles were replaced with iron ones.[28] Hydraulic steering was introduced in the 1990s, followed by electro-hydraulic systems in 2020.[26] Modern equipment such as radar and GPS was also installed.[28] However, PS Gazi, PS Teal, and PS Kiwi were decommissioned in the late '90s after catching fire while docked for repairs.[29]

Until 2022, four paddle steamers—PS Ostrich (built in Scotland in 1929),[27] PS Mahsud (1928), PS Lepcha (1938), and PS Tern (1950)—were operated by the BIWTC once a week. This was a reduction from daily trips,[26] and commercial services were eventually stopped altogether due to safety concerns, operational losses, and a lack of passengers, especially following the inauguration of the Padma Bridge.[30][26]

Seagoing paddle steamers

[edit]

The first seagoing trip of a paddle steamer was by the Albany in 1808. It steamed from the Hudson River along the coast to the Delaware River. This was purely for the purpose of moving a river-boat to a new market, but paddle-steamers began regular short coastal trips soon after. In 1816 Pierre Andriel, a French businessman, bought in London the 15 hp (11 kW) paddle steamer Margery (later renamed Elise) and made an eventful London-Le Havre-Paris crossing, encountering heavy weather on the way. He later operated his ship as a river packet on the Seine, between Paris and Le Havre.

The first paddle-steamer to make a long ocean voyage crossing the Atlantic Ocean was SS Savannah, built in 1819 expressly for this service. Savannah set out for Liverpool on May 22, 1819, sighting Ireland after 23 days at sea. This was the first powered crossing of the Atlantic, although Savannah was built as a sailing ship with a steam auxiliary; she also carried a full rig of sail for when winds were favorable, being unable to complete the voyage under power alone. In 1822, Charles Napier's Aaron Manby, the world's first iron ship, made the first direct steam crossing from London to Paris and the first seagoing voyage by an iron ship.

In 1838, Sirius, a fairly small steam packet built for the Cork to London route, became the first vessel to cross the Atlantic under sustained steam power, beating Isambard Kingdom Brunel's much larger Great Western by a day. Great Western, however, was actually built for the transatlantic trade, and so had sufficient coal for the passage; Sirius had to burn furniture and other items after running out of coal.[31] Great Western's more successful crossing began the regular sailing of powered vessels across the Atlantic. Beaver was the first coastal steamship to operate in the Pacific Northwest of North America. Paddle steamers helped open Japan to the Western World in the mid-19th century.

The largest paddle-steamer ever built was Brunel's Great Eastern, but it also had screw propulsion and sail rigging. It was 692 ft (211 m) long and weighed 32,000 tons, its paddlewheels being 56 ft (17 m) in diameter.

In oceangoing service, paddle steamers became much less useful after the invention of the screw propeller, but they remained in use in coastal service and as river tugboats, thanks to their shallow draught and good maneuverability.

The last crossing of the Atlantic by paddle steamer began on September 18, 1969, the first leg of a journey to conclude six months and nine days later. The steam paddle tug Eppleton Hall was never intended for oceangoing service, but nevertheless was steamed from Newcastle to San Francisco. As the voyage was intended to be completed under power, the tug was rigged as steam propelled with a sail auxiliary. The transatlantic stage of the voyage was completed exactly 150 years after the voyage of Savannah.

As of 2022, the PS Waverley is the last seagoing passenger-carrying paddle steamer in the world.

Paddle-driven steam warships

[edit]Paddle frigates

[edit]

Beginning in the 1820s, the British Royal Navy began building paddle-driven steam frigates and steam sloops. By 1850 these had become obsolete due to the development of the propeller – which was more efficient and less vulnerable to cannon fire. One of the first screw-driven warships, HMS Rattler (1843), demonstrated her superiority over paddle steamers during numerous trials, including one in 1845 where she pulled a paddle-driven sister ship backwards in a tug of war.[32] However, paddle warships were used extensively by the Russian Navy during the Crimean War of 1853–1856, and by the United States Navy during the Mexican War of 1846–1848 and the American Civil War of 1861–1865. With the arrival of ironclad battleships from the late 1850s, the last remaining paddle frigates were decommissioned and sold into merchant-navy service by the 1870s. These included Miami, which became one of the first Boston steamers in 1867.[33]

Paddle minesweepers

[edit]

At the start of the First World War, the Royal Navy requisitioned more than fifty pleasure paddle steamers for use as auxiliary minesweepers.[34] The large spaces on their decks intended for promenading passengers proved to be ideal for handling the minesweeping booms and cables, and the paddles allowed them to operate in coastal shallows and estuaries. These were so successful that a new class of paddle ships, the Racecourse-class minesweepers, were ordered and 32 of them were built before the end of the war.[35]

In the Second World War, some thirty pleasure paddle steamers were again requisitioned;[34] an added advantage was that their wooden hulls did not activate the new magnetic mines. The paddle ships formed six minesweeping flotillas, based at ports around the British coast. Other paddle steamers were converted to anti-aircraft ships. More than twenty paddle steamers were used as emergency troop transports during the Dunkirk Evacuation in 1940,[34] where they were able to get close inshore to embark directly from the beach.[36] One example was PS Medway Queen, which saved an estimated 7,000 men over the nine days of the evacuation, and claimed to have shot down three German aircraft.[37] Another paddle minesweeper, HMS Oriole, was deliberately beached twice to allow soldiers to cross to other vessels using her as a jetty.[38] The paddle steamers between them were estimated to have rescued 26,000 Allied troops during the operation, for the loss of six of them.[34]

See also

[edit]

- Experiment (horse-powered boat) – Horse-powered boat

- List of extant paddle steamers

- Murray–Darling steamboats

- Pedalo – Small pedal-powered recreational boat

- River cruise – voyage along inland waterways between river ports

- Roller ship – experimental and unsuccessful watercraft design using large wheels for propulsion by Ernest Bazin

- Science and technology of the Song dynasty § Paddle-wheel ships

- Steamboats of the Columbia River

- Steamboats of the Mississippi

- Steamboats of the Willamette River – Steamboats in a US river

Notes

[edit]- ^ Experience of economics: The paddle designs using diesels are tourist vessels servicing sightseeing attractions or replica riverboats and are mainly restaurants and casinos.

- ^ The namesake of Shreveport, Louisiana

- ^ Vessels operating on the Mississippi River system are referred to as "boats".

References

[edit]- ^ PW/S VELLAMO

- ^ Bernard Dumpleton (2002). Story of the Paddle Steamer. Intellect Limited. pp. 1–47. ISBN 9781841508016.

- ^ Life on the Mississippi, by Mark Twain

- ^ Evers, Henry (1873). Steam and the Steam Engine: Land, Marine and Locomotive. Glasgow: William Collins, Sons. p. 98.

- ^ De Rebus Bellicis (anon.), chapter XVII, text edited by Robert Ireland, in: BAR International Series 63, part 2, p. 34

- ^ Hall, Bert S. (1979). The Technological Illustrations of the So-Called "Anonymous of the Hussite Wars". Codex Latinus Monacensis 197, Part 1. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. p. 80. ISBN 3-920153-93-6.

- ^ a b White, Lynn Jr. (1962). Medieval Technology and Social Change. Oxford: At the Clarendon Press. p. 114.

- ^ a b Jiménez Maroto, Alfonso José (October 14, 2020). Blasco de Garay, el ingenio de la Corona de España (in Spanish). El Faro de Ceuta. Retrieved October 31, 2022.

- ^ Wootton, David (2015). The Invention of Science. New York: Harper Collins. p. 498,647.

- ^ a b Smiles, Samuel (1884), Men of Invention and Industry, Gutenberg e-text

- ^ "Musée national de la Marine: Pyroscaphe. Bateau à vapeur". Archived from the original on 2009-11-18. Retrieved 2012-07-29.

- ^ Robins, Nick (2012). The Coming of the Comet: The Rise and Fall of the Paddle Steamer. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 978-1848321342.

- ^ "Steam-boat on a new construction". The Monitor. Sydney, NSW. 21 May 1828.

- ^ Viegas, Jennifer (2010-08-24). "When Horses Walked on Water to Transport Humans". Discovery News. Retrieved 2014-04-17.

- ^ Paine, Lincoln P (1997). Ships of the World. Houghton-Mifflin. pp. 182, 350, 357, 433–434, 487. ISBN 0-395-71556-3.

- ^ "Steamboat navigation". Mississippi River Navigation. US Army Corps of Engineers Team New Orleans. Archived from the original on 2010-01-29. Retrieved 25 Feb 2013.

- ^ Ewen, William H (1988). Days of the Steamboats. Mystic Seaport Museum, Inc. pp. 27, 53, 70–71. ISBN 0-913372-47-1.

- ^ Gandy, Joan W; Gandy, Thomas H (1987). The Mississippi Steamboat Era in Historic Photographs. Dover Publications, Inc. pp. 2–3, 116. ISBN 0-486-25260-4.

- ^ "Sprague". Wheeling National Heritage Area Corp. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 25 Feb 2013.Dead link January 27, 2018

- ^ Gladwell, Andrew (2015). "Introduction". London's Pleasure Steamers. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445641584.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1965). Science and Civilization in China, Vol. IV: Physics and Physical Technology, p.416. ISBN 978-0-521-05802-5.

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books. p. 31.

- ^ Needham, 476

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Part 7, Military Technology; The Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books. pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b Nandy, Dipan (2023-12-13). "Gone are the days of paddle steamers". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ a b c d e f Mithu, Ariful Islam (2024-01-24). "The last vestige of paddle steamers: A new tourist attraction on the horizon?". The Business Standard. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ a b MacEacheran, Mike (25 February 2022). "A romantic window into a half-drowned world". BBC. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ a b Shafique, Saleh (2022-05-20). "The last water rockets". The Business Standard. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Parveen, Shahnaz (2010-12-01). "'Rockets' running out of steam". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Shwapan, Anisur Rahman (14 January 2023). "Rocket-steamer service: 150-year-old tradition abandoned due to loss". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- ^ Men of Iron : Brunel, Stephenson and the Inventions That Shaped the Modern World by Sally Dugan ISBN 978-1-4050-3426-5

- ^ Morriss, Roger (1997). Cockburn and the British Navy in Transition: Admiral Sir George Cockburn 1772-1853. Liverpool University Press. pp. 251–252. ISBN 978-0859895262.

- ^ "USS Miami Civil War Union Navy".

- ^ a b c d Plummer 1995, p. 3

- ^ Robins 2012, pp. 145-146

- ^ Robins 2012, pp. 149-150

- ^ "Dunkirk - Operation Dynamo 1940". www.medwayqueen.co.uk. Medway Queen Preservation Society. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ Plummer 1995, pp. 28-29

Bibliography

[edit]- Clark, John and Wardle, David (2003). PS Enterprise. Canberra: National Museum of Australia.

- University of Wisconsin–La Crosse Historic Steamboat Photographs Archived 2010-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Dumpleton, Bernard, "The Story of the Paddle Steamer", Melksham, 2002.

- Plummer, Russell (1995). Paddle Steamers At War 1939-1945. GMS Enterprises. ISBN 1-870384-39-3.